Making classification relevant

Victor Heng, Outdoor Learning Programme Developer, Natural History Museum

Classification to better support biology education

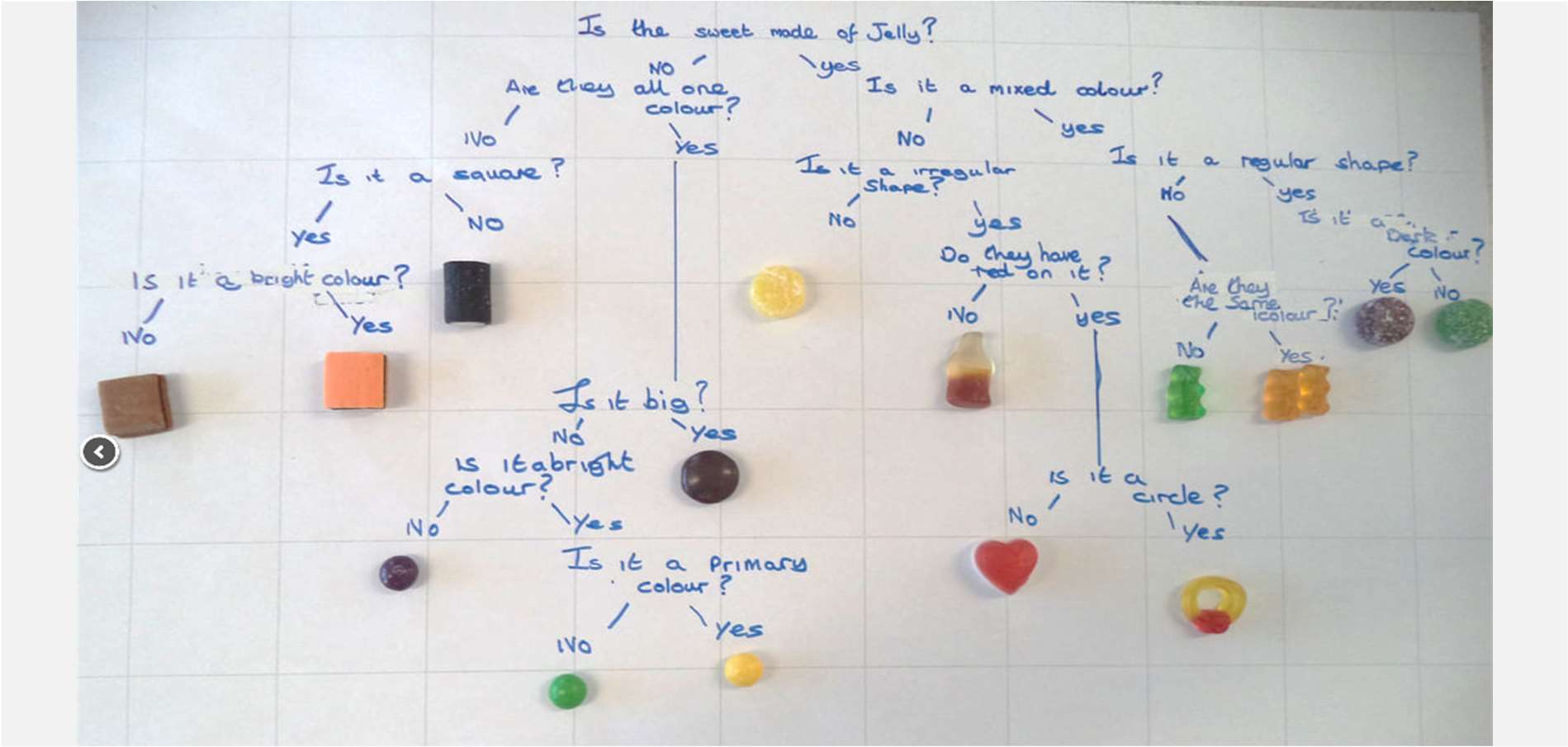

A favourite initial activity is to sort and classify sweets or biscuits. Using materials like this has the benefit of improving engagement (who doesn’t like sweets and biscuits?), but has downsides.

1. They are manufactured products, so custard creams are made to be as consistent as possible. The exercise overlooks natural variation. Using natural materials to introduce classification is more subject relevant, and builds in an opportunity for students to encounter

natural variation. Developing an awareness of variation prepares students for learning about evolution, and breaks down the essentialist understandings which students need to overcome when understanding how species change over time.

Good options for natural materials include:

- leaves from lawn ‘weeds’

- flowers (from lawn ‘weeds’ or cut flowers)

- fruit

- invertebrates

Use of natural materials also prepares students to learn about related topics in science. For example using flowers for a classification activity can prepare student for learning about the details of plant reproduction. This may free up time which would have been spent learning vocabulary, which can then be spent on learning about another topic in more depth.

2. The exercise of sorting or creating a key is often done for the sake of doing the exercise. Beyond it being an engaging (and tasty) thing to do, students may not understand why it is relevant.

Classification for a purpose

Informing decisions or solving problems

Introducing a scenario where classification is a part of solving the problem or informs choice of solution makes the exercise more meaningful and relevant. In the biscuits and sweets example, perhaps students are developing a snack classification system to determine which sweets are suitable for certain dietary requirements (i.e. nut allergies, celiac disease etc.) As part of the Natural History Museum’s Urban Nature Project, several new sessions were developed including one where students are tasked with providing advice to a farmer who is having problems with their strawberry crop. The initial suspicion is that insects may be damaging the strawberries by feeding on the plants. By classifying insects in a sample ‘from the farm’, students find that there isn’t an unexpected number of herbivorous insects, but there are very few flies.

farmer who is having problems with their strawberry crop. The initial suspicion is that insects may be damaging the strawberries by feeding on the plants. By classifying insects in a sample ‘from the farm’, students find that there isn’t an unexpected number of herbivorous insects, but there are very few flies.

Initial solutions suggested included use of insecticides, or covering the plants with netting or a glasshouse. After the classification activity, students reflect on those solutions and determine that none of their initial suggestions would help the farmer and may have made the problem worse. The use of the key and correctly classifying insects is made relevant because it informed a choice which could have had meaningful (though imaginary here) consequences.

Identification or conveying information

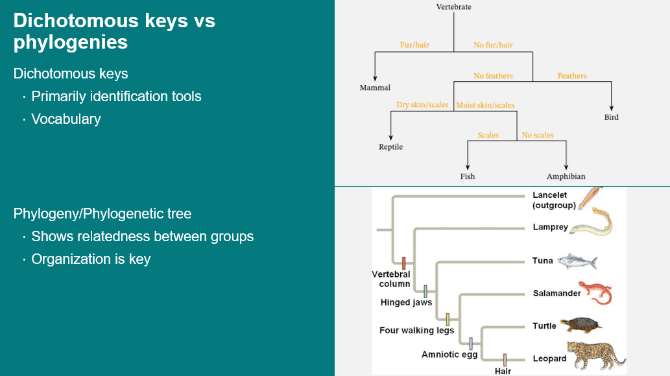

The key is a way of structuring information. The structure can be used for a variety of purposes. Often it is initially used for identification. However it can also be revisited in the context of evolution to convey information about shared features and evolutionary relationships.

Revisiting branching keys and rearranging questions may lead to more meaningful grouping of information. In the example below, the questions have by chance grouped together liquorice all sorts, but fruit pastilles have been ended up far apart. The key works from the perspective of identifying sweets, but other ways of organizing the key might allow it to convey additional information.

Contributing to science

Most citizen/community science projects involve crowdsourcing data collection, which often involves some classification to determine if the information is relevant to the project.

Zooniverse (www.zooniverse.org) – Has many projects asking the public to tag photographs to identify whether they contain relevant animals or plants, and what type.

UK Pollinator Monitoring Scheme (https://ukpoms.org.uk/) – Monitor pollinators by conducting Flower-Insect Timed Counts (FIT counts) where students will need to classify insects visiting a patch of flowering plants in a 10-minute period.

NHM Survey calendar for beginners – Calendar of UK biodiversity monitoring schemes suitable for beginners.

The potential of direct partnerships between schools and nature reserves

Development of NHM’s new Biodiversity in Action session has also demonstrated that students can be pretty good at insect classification. Schools could work together with local nature reserves or parks on monitoring biodiversity, with samples being collected by the sites and sent to schools where classes can do an initial sort of the sample before it gets forwarded on to entomologists for further study.

For example, Royal Parks manages several of London’s largest green spaces, including Richmond Park which is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in part because of its deadwood microhabitats. These are significant habitats for many beetle species, so Royal Parks have been collecting samples of insects from the park to study what beetle species may be present. Separating out the beetles from these samples is not a difficult job, but it is time consuming. Because of this, Royal Parks have not been able to process the samples to send on for further study.

Local schools could very quickly process these samples with reasonable accuracy. Session trials at the NHM have show that students at year 6 can be up to 70% accurate in their sorting within a single 45-minute session. It is very likely a context like a nature club, where students could have more time to practice and become familiar with insects, could get to nearly 100% accurate pretty quickly.

Find resources for monitoring biodiversity monitoring at your school on the National Education Nature Park

website (https://www.educationnaturepark.org.uk/).

Feel free to contact with questions! v.heng@nhm.ac.uk