Frontier Science: Multi-representational learning: Beyond dual coding

Shaaron Ainsworth, Professor of Learning Sciences, University of Nottingham, School of Education

In my presentation, I explored why multiple representations are essential for effective science learning, while critiquing some commonly cited, but in my view problematic, rationales for their use. I suggested that three common weak reasons are: learning styles, dual coding, and cognitive load reduction. The learning‑styles argument is problematic because there is little evidence that matching instruction to preferred modalities improves learning. Dual coding is frequently oversimplified; although students often learn better from words and pictures together, many boundary conditions influence whether the combination is effective, and the modality of input does not determine the modality of code. Similarly, claims that multiple representations reduce cognitive load overlook the complexities of working memory, including the need to integrate representations and the productive role of effortful processing.

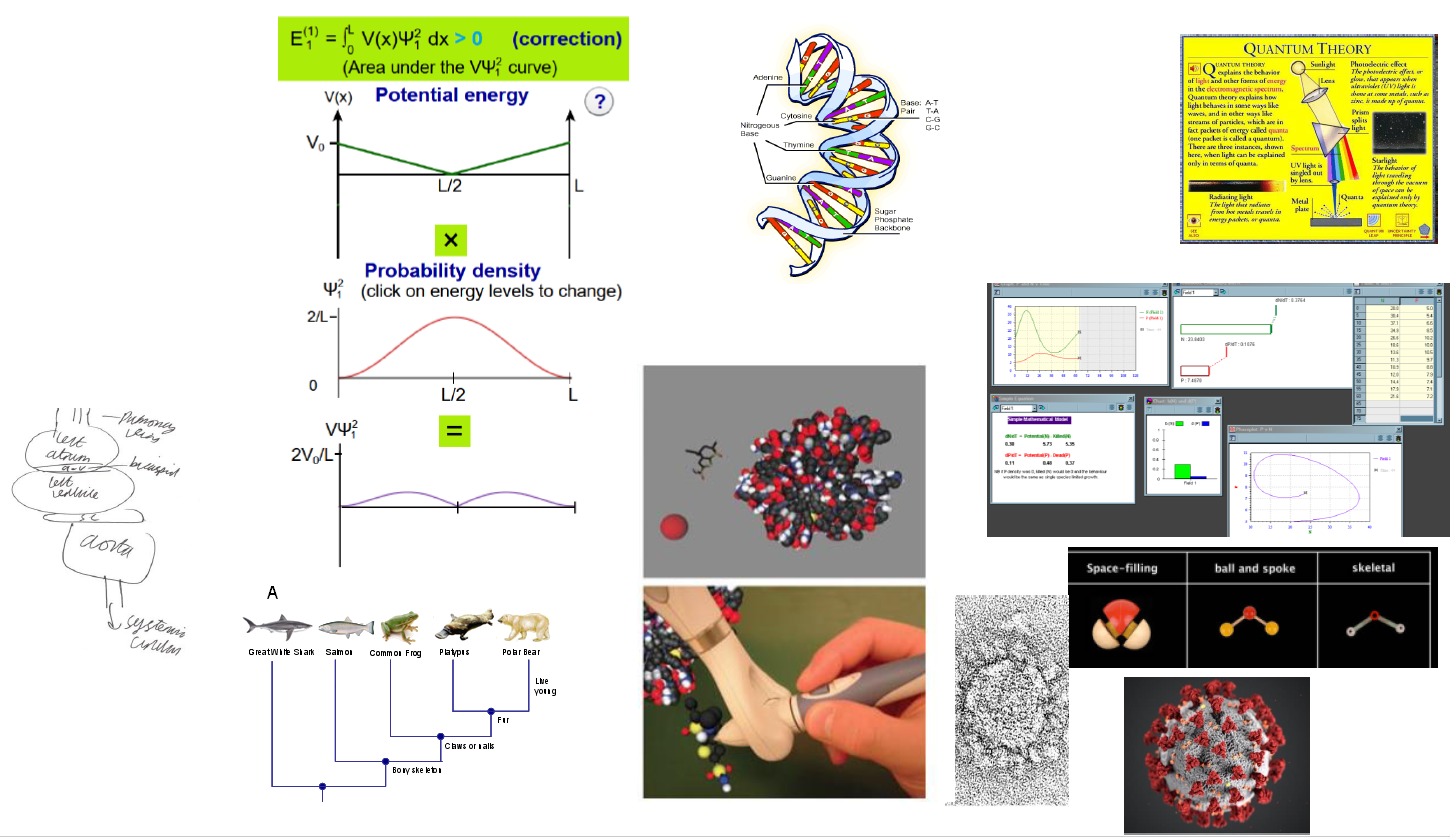

I then presented five stronger reasons for using multiple representations. First, science itself is intrinsically representational: models, diagrams, graphs and symbolic systems are central to scientific reasoning, so learners must develop representational competence. Second, different representations possess different properties, making them suitable for different tasks. Third, they help students interpret unfamiliar or abstract concepts if one representation helps learners understand a second one. Fourth, integrating representations supports abstraction by helping learners distinguish between surface features and underlying principles. Fifth, constructing new representations from existing ones (such as text or another visual) promotes deeper understanding and transfer.

However, there are challenges that students must overcome: recognising the inherent complexity of representations; coping with suboptimal or detecting decorative materials; and understanding that learning depends not on the representations themselves but on what students do with them. Effective learning involves active and ideally constructive engagement. Students should be talking about, gesturing toward, analysing, critiquing, and re-representing information rather than passively viewing representations

The overall message is that representations are powerful tools for learning, but only when students learn both with them and about them. Teachers can help learners develop the skills needed to interpret, construct, translate, and reason with multiple forms of representation.