Responsible use of AI in science education: A framework for impactful but responsible application of AI in your school

Alex More, Education Consultant & Penelope Sharott, OUP

Responsible use of AI – Alex More

Alex opened the talk with reflections on how AI is perceived by teachers and by itself. Framing the provocations around What does this technology want? Alex illustrated how AI as a technology is being received by both teachers in the classroom and students at home.

Drawing from the recent DfE Curriculum and Assessment Review (CAR), the talk foregrounded the changes on the horizon, with a specific focus on digital skills, critical thinking and what teachers can do to prepare students for this future. Drawing on language from the CAR, Alex explored some of the tensions within it. For example, how can a document that claims to want to prepare students for a rapidly changing world, infused by AI, achieve this by leaving the curriculum intact? By understanding the intentions, we can begin to see how AI might fit into the fabric of our existing curricula.

Alex then touched on some of the risks around AI and how the CAR explicitly links AI to misinformation and online harms.

Oxford University Press’ AI Framework - Penny Sharott

It was in response to some of the risks that Alex touched on above that Oxford University Press (OUP) decided to put together an AI Framework to ensure that they are using AI in such a way as to support their Education mission “to deliver demonstrable impact by empowering every learner and education to reach their potential.” Penny outlined OUP’s collaborators in pulling together their AI framework: Chris Goodall of the Bourne Education trust who co-founded AI in Education with Epsom College and Educate Ventures, led by Professor Rose Luckin. Chris represented teachers and brought an understanding of the reality of classrooms, whilst Rose brought more than 30 years' experience developing and researching AI for education.

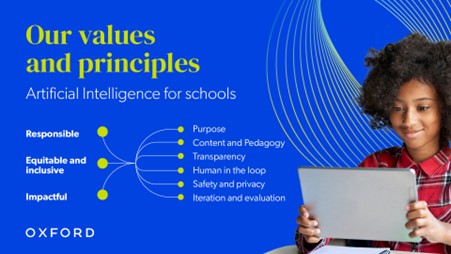

At the heart of the framework are a set of values and principles intended to guide ethical and effective AI implementation. The values state that AI should be responsible, equitable and inclusive and impactful.

The responsible value requires that OUP first consider why AI is being introduced and what implications it may have for learners, teachers, and the wider school community. It demands respect for the professional expertise of teachers and a strong commitment to safeguarding. Equitable and inclusive refers to the requirement that AI tools work across a range of devices, support diverse learner needs, and avoid embedding bias. The value of impact emphasises the need for a clear purpose and a demonstrable link to educational outcomes, supported by thoughtful learning design, strong content expertise, iterative development processes and the keeping of a human in the loop.

The accompanying principles articulate how these values translate into practice. Purpose sits at the forefront, captured succinctly by Rose Luckin’s caution that “just because you can doesn’t mean you should.” AI should be adopted only where it meaningfully addresses a real educational challenge and where it represents the best available solution. Content and pedagogy remain central: AI performs most effectively when anchored in high‑quality, curriculum‑specific material and structured around sound pedagogical design. Transparency is essential for trust, requiring clarity about how AI tools operate, how data is used, and where limitations lie so that teachers can exercise professional judgement. The principle of maintaining a human in the loop recognises that, particularly in higher‑stakes contexts such as assessment or curriculum design, teacher oversight remains indispensable. Safety and privacy must govern all stages of design, ensuring that personal data is protected and harmful content is filtered out. Finally, an iterative approach to development—testing tools internally, then externally with small, closed groups, before testing more widely —ensures that AI products remain safe, effective, and aligned with user needs.

These values and principles offer teachers two forms of reassurance: confidence in the tools that OUP are developing, and a practical checklist for assessing any AI product they may encounter, regardless of the provider.

OUP’s research into “Teaching the AI-Native Generation”

Given the complexities and risks associated with student use of generative AI, OUP’s initial development has focused on teacher‑facing tools designed to support planning, differentiation, and assessment.

This caution around putting AI in the hands of students was justified by OUP’s research report “Teaching the AI-Native Generation” which surveyed 2,000 secondary students across the UK. It revealed that fewer than half feel confident in identifying AI‑generated misinformation, signalling a need for teacher mediation and explicit development of critical AI literacy. Meanwhile, six in ten students believe that AI use has negatively affected at least one aspect of their schoolwork such as limiting their creative thinking. More positively, nine in ten report that AI has helped them develop new skills, particularly in problem‑solving and communication.

OUP’s early trials with AI

Penny then outlined some AI tools that OUP have been trialling with schools. These included generators which allow teachers to generate resources like multiple choice questions by drawing on content from OUP’s courses. These would allow teachers following these courses to generate resources that cater to their students’ needs, are founded in trustworthy content and aligned with their curriculum. Penny also showed an AI marking tool which can give a mark and feedback on a student answer to a longer, exam-style question. This marking would be reviewed by a teacher before being released to the student. These AI solutions are currently being piloted with a closed group of schools and Penny invited attendees to register their interest in being involved in future trials.

What can we do as teachers and leaders to prepare students for this future?

Alex closed the session by bringing attendees back to the above question which he had posed at the start. His intention was to open the door to conversations about the future direction of travel without claiming to know the destination. In essence, the provocations called into question the silences, those parts of the conversation that are not being spoken about. The intention here was to leave people curious about where the teaching of AI will sit. Currently, the CAR positions itself within the silo of Computer Science, but is this restrictive? Closing with some insights into how Ofsted and the exam boards are approaching AI felt like a natural endpoint for a talk that covered some ground and left people curious yet informed, for now.

References:

Curriculum and Assessment Review final report - https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/curriculum-and-assessment-review-final-report

AI in Education - https://www.ai-in-education.co.uk/

Educate Ventures - https://www.educateventures.com/

Oxford University Press’ AI Framework for Education - https://global.oup.com/education/content/ai-and-education/?region=uk&srsltid=AfmBOoopEp2YBgl9tb6cRBLTNWwQrLDOpD62tQyEqemRfEHij16AtSoS

Oxford University Press’ Teaching the AI-Native Generation Report - https://corp.oup.com/spotlights/teaching-the-ai-native-generation/